Here’s what I read: This piece from June of 2020 in Nature, about what the data says about police departments and racial bias

Here’s what I learned: Many police departments include members of terrorist organizations. They must be removed.

Are police officers racist? This is an essential question that confronted me as I began to do research for an upcoming podcast recording. (I am guest hosting a couple episodes of “The debate,” a new show from Newsweek that hopes to demonstrate that civil discourse is possible, even between people who strongly disagree.)

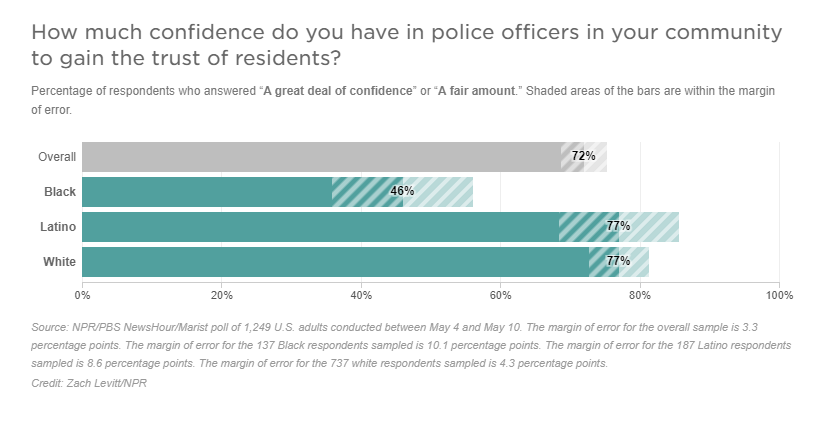

Frankly, opinion polls don’t offer a lot of enlightenment on this issue, as a person’s answer to the question—are the police racist—depends almost entirely on their race and political party. Only 25% of white Americans think officers are harder on people of color than white people (the data proves otherwise quite definitively) and 91% of Republicans think the police will be able to restore trust with local communities, while Democrats are much more skeptical.

So, I decided to leave public opinion out of it and rely solely on the data available. Not surprisingly, there is not a lot of credible research into the values that officers’ hold. Certainly, if you ask a police officer, “Are you racist?”, chances are very good that they’ll say “no.” Then again, that’s true of just about everyone you meet. Even David Duke, former grand wizard of the Knights of the KKK, claims that he is not racist.

Here’s an excerpt from a recent related article:

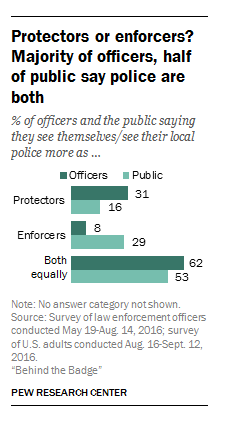

However, Pew Research Center conducted a survey in 2016 in which they asked a group of nearly 8,000 police officers the same questions they asked a nationally representative group of about 4.500 civilians, and the differences in opinion were marked. For example, most officers believe that the killings of unarmed Black civilians in recent years are “isolated incidents”, while most of the public thinks they are “signs of a broader problem.”

Also interesting is the answers to the following question from Pew Research Center: “Has the country made the changes needed to give blacks equal rights with whites?” 80% of police officers said yes, while over half of the public said no. Even more striking, 92% of white police officers answered yes to this question.

So, there is a significant disconnect between the views of most police officers and the public on racial progress in this country and on the role of the police in our lives. But again, I find it more useful to not rely on opinion polls in order to determine whether anyone, law enforcement or not, is racist.

How do we define “racist,” anyway? Since I’ve already written about this, I’ll include an excerpt from my new book, Speaking of Race, that comes out in November:

There are many definitions of “racist,” and none that I’ve seen are entirely wrong. You could say a racist is someone who discriminates against others who appear to belong to a different race. For the purposes of this book, this definition doesn’t work, as it absolves people of being racist until they take concrete action to hurt another person. They can harbor very racist beliefs, but until they exclude Asians from their group or refuse to hire a Black employee, we don’t consider them racist.

Yet the racist behavior that is most common and affects the largest number of people is not the behavior that breaks laws, but that which harms others incrementally: the casual racist comments thrown out over dinner, the choice to look at your phone while a person of color is speaking in a meeting, the unconscious decision to avoid looking at Black people as they pass you on the sidewalk. Those behaviors are rooted in racist beliefs. Therefore, in this book, I will use this definition: a racist is someone who makes assumptions about another person (either positive or negative) because of their perceived race or ethnicity.

By that definition, we are all racist.

In one sense, we are all racist, that includes police officers, even the Black ones. If we want to find proof, though, I believe we have to study measurables. That means, we must look to disparities in the way that white civilians are treated versus Black ones. The evidence in this area is overwhelming: Black people are 3.23 times more likely to be killed by police than white; Blacks are 95% more likely to be stopped by police (when you account for time spend on the road) and 115% more likely to be searched during a traffic stop, even though contraband was more likely to be discovered in vehicles owned by white drivers. The stop and frisk data from New York City was damning, in that nine out of ten people stopped by officers were innocent and more than 80 percent of people stopped were Black or Latino.

Conservatives like Heather MacDonald may claim that “there’s no evidence of widespread racial bias” in police departments and that police racism is a “myth”, but she’s simply wrong. There is ample evidence of wide disparities in the way civilians are treated by police in all 50 states.

Source: 10 things we know about race and policing in the U.S.

Even more arresting (pardon the pun), are the reports from other law enforcement agencies about links between local police departments and white supremacist groups, something the FBI has tracked for decades. In 2006 an intelligence assessment from the FBI warned that “white supremacist groups have historically engaged in strategic efforts to infiltrate and recruit from law enforcement communities” and officers were willing to “volunteer their professional resources to white supremacist causes.”

In 2015, the FBI created a counterterrorism policy guide that was leaked to the media. It warned federal agents that “domestic terrorism investigations focused on militia extremists, white supremacist extremists, and sovereign citizen extremists often have identified active links to law enforcement officers.”

I ask you, if the FBI learned that members of ISIS or al Qaeda had infiltrated local police departments, do you think the government would take action to remove those officers? Of course they would, as those people would pose a clear danger to the public and their loyalty to the communities they would serve would be in question.

The same logic should be used to remove any officer with ties to a white supremacist organization, as the FBI has said they pose a “persistent threat of lethal violence,” and since the year 2000, far-right groups have caused more deaths in the US than any other category of domestic terrorism.

Before you argue that police officers have the constitutionally protected right to associate with whatever groups they like and the freedom to say whatever they believe, I suggest you examine the decision of the Alabama Supreme Court in the case of Oladeinde v. City of Birmingham, a decision that was upheld by the 11th Circuit. The judges decided that some restrictions on speech and associations are allowed for law enforcement because of a “heightened need for order, loyalty, morale and harmony.”

In the FBI’s 2006 assessment, the agency summarized Supreme Court precedent on this issue and noted: “Although the First Amendment’s freedom of association provision protects an individual’s right to join white supremacist groups for purposes of lawful activity, the government can limit the employment opportunities of group members who hold sensitive public sector jobs, including jobs within law enforcement.”

Which brings us back to the question that launched my research and this newsletter: are police officers racist? I think the answer is yes, both to the extent that all Americans have racial biases and that significant disparities exist in the way civilians are treated by police according to their perceived race. Finally, there is a documented history of links between law enforcement and white supremacist organizations, something that should concern anyone who wants to prevent acts of terrorism on American soil.