What I read: A tweet from @NoContextBrits that was simply the following image.

What I learned: We have to stop pretending it’s easy to tell people apart if they belong to a race that is not our own.

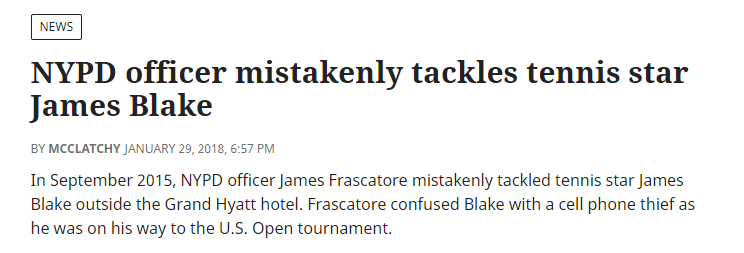

I’ll admit that I posted this screen grab on Twitter with a snarky remark and intended to forget about it completely as another example of white people who can’t distinguish one Black person’s face from another’s. There are so many examples of this, I could list them ad nauseam: there was the KTLA reporter who thought Samuel L. Jackson was Laurence Fishburne, the BBC report on Kobe Bryant’s death that used footage of LeBron James instead of Bryant, George Stephanopoulos mistaking actor Morgan Freeman for basketball legend Bill Russell, the NBC affiliate that showed singer Seal’s picture during a report on actor Michael Clarke Duncan’s death, or when CNN anchor Erin Burnett accidentally identified members of the sorority Zeta Phi Beta as members of a gang.

CNN’s Erin Burnett Mistakes Zeta Phi Beta Sorority Members As Gang Bangers

But hours after I posted the photo of two British girls posing with former soccer star Chris Kamara and believing they were snapping a selfie with a Grammy award-winning Black musician, I was still thinking about their mistake. In the end, I decided to write about it, although I’m not here to shame them for their error or call them racists.

The truth is, there is solid scientific evidence explaining why a white person might think Black people resemble each other, or Asian faces are difficult to distinguish. What’s going on might be racism, as in “they all look alike,” or it could be something else. The phenomenon of mistaking one person of color for another (or, really, for misidentifying anyone who doesn’t share our racial identity) is called “cross-race effect.”

Researchers believe the roots of this cognitive error lie in the human tendency to categorize people, especially strangers, by their appearance, their social class, their language, etc. Scientists at Miami University say their research strongly implies that “the cross-race effect is due, at least in part, to this ubiquitous tendency to see the world in terms of these in-groups and out-groups.”

That’s just a recent study, by the way. Scientists have documented this phenomenon for decades. At a very young age, children begin showing preferences for the kind of facial features they see most often, for blue eyes over brown, for example, or light skin over dark. Research shows that a child who sees mostly white people will tend to focus on hair and eye color when evaluating someone’s appearance. A Black child will likely notice subtle differences in skin color.

If a child is not exposed to people of a different race, they will have more difficulty remembering their faces or even identifying them. Psychologist Roy S. Malpass says that when someone says, “They all look alike to me,” that claim is both credible and possibly true. It’s not just white people who make this mistake, of course. Genetic psychologist Gustave Feingold first coined the term “cross-race effect” more than a hundred years ago. He wrote in 1914 that “to the uninitiated American, all Asiatics look alike, while to the Asiatics, all White men look alike.”

I have a tough time telling the difference between Margot Robbie and Jaime Pressly, for example, and once told my friend that I thought Zachary Quinto was excellent in “New Girl.” Quinto, of course, is not in “New Girl”; that’s Max Greenfield, who looks like Quinto’s twin to my eyes. How are Katy Perry and Zooey Deschanel not related?

This is sticky because, although there is a reasonable scientific explanation for why white people think actress Lucy Liu looks like journalist Lisa Ling (they don’t look alike to me), that doesn’t make it less hurtful to people of color who are so often confused for one another. Two men told the New York Times that they were mistaken for each other so often, they hung a sign near their desks that tracked the days since a colleague mixed them up. “It kind of makes you feel invisible,” Nicholas Pilapil said.

If you spend a few minutes on social media, you will find stories about misidentification from hundreds, if not thousands, of BIPOC people.

Research into the cross-race effect shows that white people are more likely to make this mistake than others are, partly because most children of color are exposed to a lot of white faces from a very young age. This is one reason it’s so important that movies and TV shows include a wide range of skin colors and hair styles and body types and abilities.

The bare fact is the U.S. is highly segregated. Research carried out by social scientists at Brown suggests that most of us live in neighborhoods that are divided on racial lines, and we always have. The researchers discovered that “people of different races don’t just live in different neighborhoods — they also eat, drink, shop, socialize and travel in different neighborhoods.”

The lead study author, sociologist Jennifer Candipan, was dismayed to find that we are more segregated than most people realize, not only working in places where people look like us and have similar backgrounds, but also going to restaurants where we encounter people with similar racial backgrounds and coffee shops where we don’t have to interact with people who are too dissimilar from ourselves.

This kind of segregation contributes significantly to inequity and injustice, but it also means that we don’t see enough diverse faces and are therefore at higher risk of mistaking one person for someone else. As educational consultant Ali Michael wrote in 2020, calling a person of color the wrong name is “more than just awkward. It is a microaggression.”

If the mistake is a product not of bias, but of limited exposure, you might ask, how could it be classified as a microaggression? Because it’s something that overwhelmingly happens to people of color who are already made to feel excluded and invisible by a society that values white concerns over theirs. As Ali Michael wrote, “When you call an Asian-American student by another Asian-American student’s name, you communicate age-old tropes such as ‘All Asians look alike’ or ‘Asianness is not normal’ or ‘I can’t tell you apart.’ The weight of those tropes, coupled to the weight of the cumulative effect, is what transforms a mistake into a microaggression.”

The issue moves into much more dangerous territory when facial recognition is a matter of criminal justice. Without delving too deeply into this subject, I’ll simply say that facial recognition software is incredibly inaccurate when it comes to Black faces and that neither white police officers nor white bystanders can be fully trusted to identify specific Black individuals.

https://www.star-telegram.com/news/article176874996.html

Because it’s both insulting and dangerous for white people to mix up people of color, it’s crucial that action be taken to prevent this mistake from happening in the future. The first step is to admit that you are not great at distinguishing people who belong to another race. Don’t deny it, because that prevents you from addressing the issue and improving your skills. Own up to it.

If you call someone the wrong name, don’t try to pretend it didn’t happen and never speak of it again. Apologize and make damned sure you get it right next time. You can say, “I’m so sorry. Sometimes I screw up people’s names and I know it can be hurtful. It will not happen again.” Lying to yourself and others by pretending you don’t mix up people’s faces and names is not helpful.

I’m sure the denial is somewhat connected to fear that you’ll be labelled racist. But one mistake doesn’t make you a racist; repeated mistakes that injure or insult a person of color do. Remember that a microaggression is damaging not because of its severity. By definition, microaggressions are minor. They become harmful because they are repeated again and again, and the accumulation of minor injury eventually becomes a major injury, like a slow drip of water that erodes stone over time.

Even if you were raised among people who looked like you and shared your racial history, it’s not too late to hone your skills. We have known about this problem since at least 1914. Isn’t it time to acknowledge the issue honestly and stop pretending white people don’t have trouble telling one Black or Asian person from another?

Another study on cross-race effect, this one conducted in 2019, demonstrated that the ability to process different faces relies on the visual cortex. Using a functional MRI, scientists were able to prove that white subjects were much more sensitive to physical differences in photos of white people than they were to photos of Black people. (The sample pool was quite small: just 17 white participants looking at photos on a digital monitor.)

But while the results were both predictable and disappointing, studies like this one do provide glimmers of hope. The lead author, psychologist Brent Hughes, said, “These effects are not uncontrollable. These race biases in perception are malleable and subject to individual motivations and goals.”

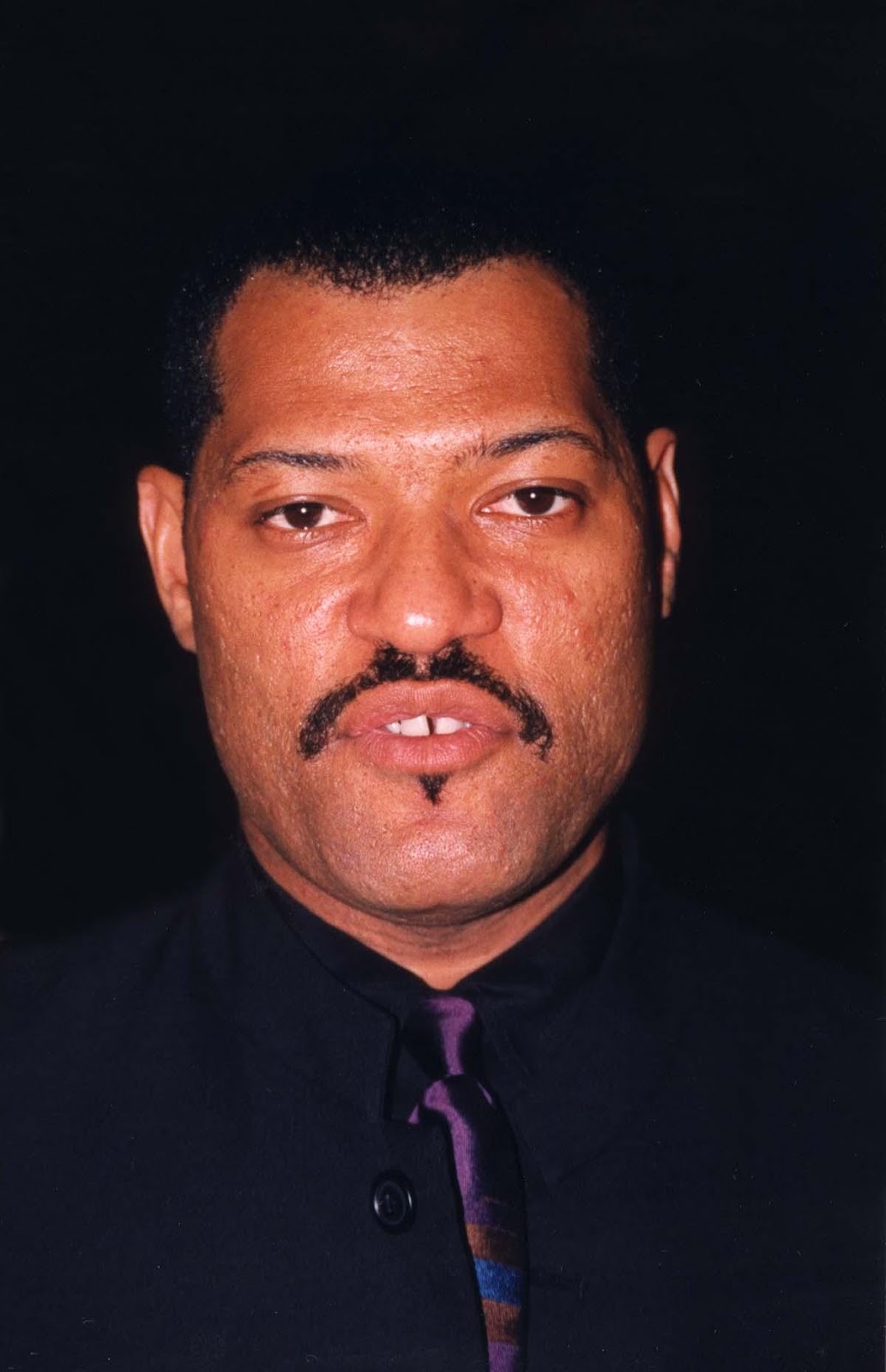

In other words, you can be forgiven for calling someone the wrong name once, but not for doing it repeatedly. You can counteract the cross-race effect by simply exposing yourself to a broader range of racial features. Watch movies with predominantly Black casts, look carefully at the photos of people from China and the Philippines and notice the subtle differences in skin tone and eye shape. Look at these photos of Samuel L. Jackson and Laurence Fishburne.

I’m willing to bet that if you spend some time actually looking at their faces, you will notice a lot of differences. Jackson is a much darker shade than Fishburne. Fishburne has a more elongated face, while Jackson’s lips are darker, thinner, and wider. Look at the difference in their cheeks and their eyes and their brows. They look nothing alike to me. I bet that if you study their faces, you will realize there is no resemblance.

But, if you do mix them up in the future, don’t laugh it off and say, “Oops! Honest mistake.” Doing it once is a reflection of your upbringing and lifestyle, while doing it repeatedly is racism borne of indifference. Care enough to recognize faces that are different from your own.

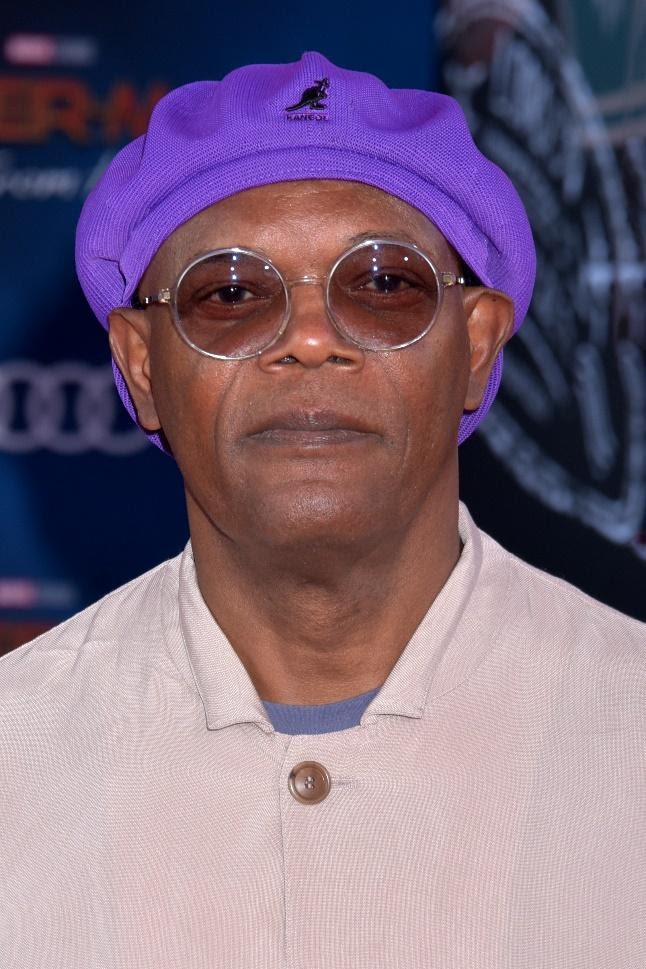

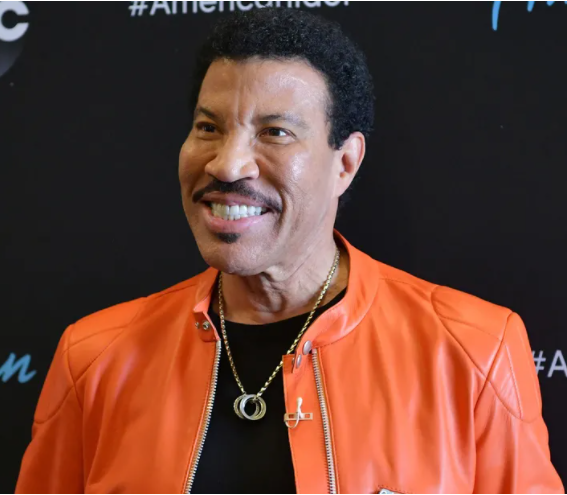

And one last thing… this is Lionel Richie.

This is not.